Talented restorationists like Ebby DuPont nurture tired old wooden boats back to their head-turning original glory.

Wooden boats have an organic appeal. But beneath the gleam resides all the toil, effort that can be counted in sheets of sandpaper, brush strokes toward perfection, and time spent rounding up dust. The true craftsman loves the battle, and dreams about the projects that lay ahead. For some, refinishing the brightwork just isn’t enough. These are the restorationists, a loosely affiliated, guild-like cluster of small-craft perfectionists. Most have mastered multiple talents, can change hats from carpenter and shipwright to painter or mechanic, and are always on the hunt for a derelict boat with a great pedigree. They search for lost gems, some left to rot away, that are important examples of nautical heritage. The freelance restorationist helps keep history alive.

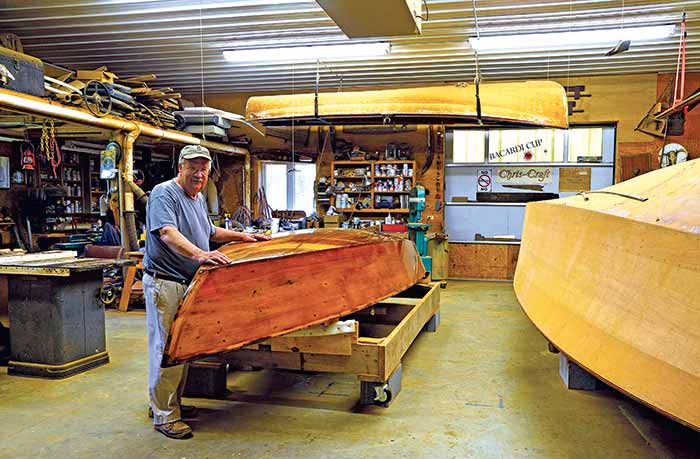

Master Craftsman

Ebby DuPont, a Maryland sailor with a passion for wooden runabouts, pursues a mahogany renaissance. His tightly focused, somewhat frenetic approach to retirement has been centered around finding, restoring, and displaying iconic wooden speedboats. The success of his endeavor is helping to keep an important slice of motor boat history alive. Over the years, we’ve watched Ebby turn hulks into boats that look like new, as a mini nautical museum takes shape alongside his shop.

Ebby grew up around boats and discovered Chesapeake Bay with a tiller in hand. His familiarity with wooden sailing dinghies, skiffs, runabouts, and sailing yachts of Maryland’s Eastern Shore conjured visions of an era where log canoes, skipjacks, and bugeye ketches graced the waterfront. Here, wooden boats have not yet been completely relegated to antique status.

For more than three decades, Ebby ran a thriving historic-home restoration company he founded. Along the way, he received his share of Historical Society awards and recognition. So it came as no surprise that when it was time to retire, he opted to expand his shop rather than shop for the figurative rocking chair.

Old Vs. New School

Ebby is a one-man band. Once he’s acquired his next project boat, he estimates the scope of the work and, more often than not, faces a complete rebuild. Through experience, he’s learned the value of holding on to the rotten planks, sprung frames, and corroded pieces of hardware, because each part carries clues not seen on the builder’s plans. They often become patterns used to help re-create what’s missing and ensure his restoration is as close to the original as possible.

Today’s epoxy glues and polyurethane adhesive/sealants are a vast improvement over what was available on the chandlery shelf 70 or 80 years ago, but there’s a debate among restorationists as to whether new materials should be used. Ebby’s opinion is that if the modern adhesive makes it a better boat, go ahead and use the high-tech adhesive, because it will improve how things are held together, extending the life of each reincarnation.

In many cases, missing parts are hard to find. But old-boat aficionados have greatly benefitted from the internet and a global interest in restoring old boats. Not only does it make tracking down a vintage 1928 Chris-Craft bow cleat or step pad a little easier, but it often links a restorationist with like-minded souls elsewhere in the world. In some cases, a specific part can’t be found, but today there are small machine shops with 3D printers and CAM tools that can cost-effectively make a new part.

Labor Of Love

Each project begins with a major effort to stabilize the shape of the boat using a carefully built frame or strongback. It provides transverse and longitudinal supports during disassembly, even as planks are removed and replaced. Many of these early mahogany hulls were double planked, making a partial repair as challenging as a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. A layer of canvas and a lead-based sealant was often used between thin planks. Fortunately, there are better performing, less hazardous sealants available today.

Engines are another facet of concern for most marine restorationists. Ironically, there are lighter, more powerful, smoother-running, and much more reliable motors on the market today. But part of the Chris-Craft lure is the search for big iron — straight 6- and 8-cylinder gas engines. Most of these long-stroke, low-compression-ratio engines are branded with a Chrysler logo. Wide open, they spoke with authority and burbled just the right sound when dawdling toward or away from the dock. The low top RPM, unimpressive weight-to-horsepower ratio, and bane of a 6-volt electric system were all part of the package.

Ebby and his wife, Nance, have taken the show on the road, trailering their boats from Florida to New York’s Adirondacks and collecting silver along the way. When they’re back home, friends regularly drop by to slow progress and engage Ebby in arcane boat talk. On my last visit, he was finishing up the restoration work on a Comet Class centerboard sailing dingy that he and one of his daughters planned to race in local regattas. He pointed out how carefully, way back in the 1930s, the original builder had spiled in each straight-grained plank and how fine craftsmanship stands the test of time.

Whether it’s power or sail, the boats leaving Ebby’s workshop continue to be symbolized by tight seams and smooth, mirror finishes — a worthy glimpse at mahogany’s golden era.

His workshop and studio are both works of art. I count myself privileged and honored to be able to call him a friend who I get to hang out with every now and then (mostly to get advice). On my return to the western shore I get to happily reflect on what I’ve just learned. I’m one lucky guy. Ralph